‘For me, drawing lights a way. What we bring into manifestation becomes an entity of its own. Where is true North? Drawing helps me map unknown territories.’

~ Claire Beynon

The carpet is loop-pile, thick cream wool which feels just-woven and washed, I’ve sunk down onto it, as if falling is natural, like the end-flight of a dandelion seed. Here. Here.

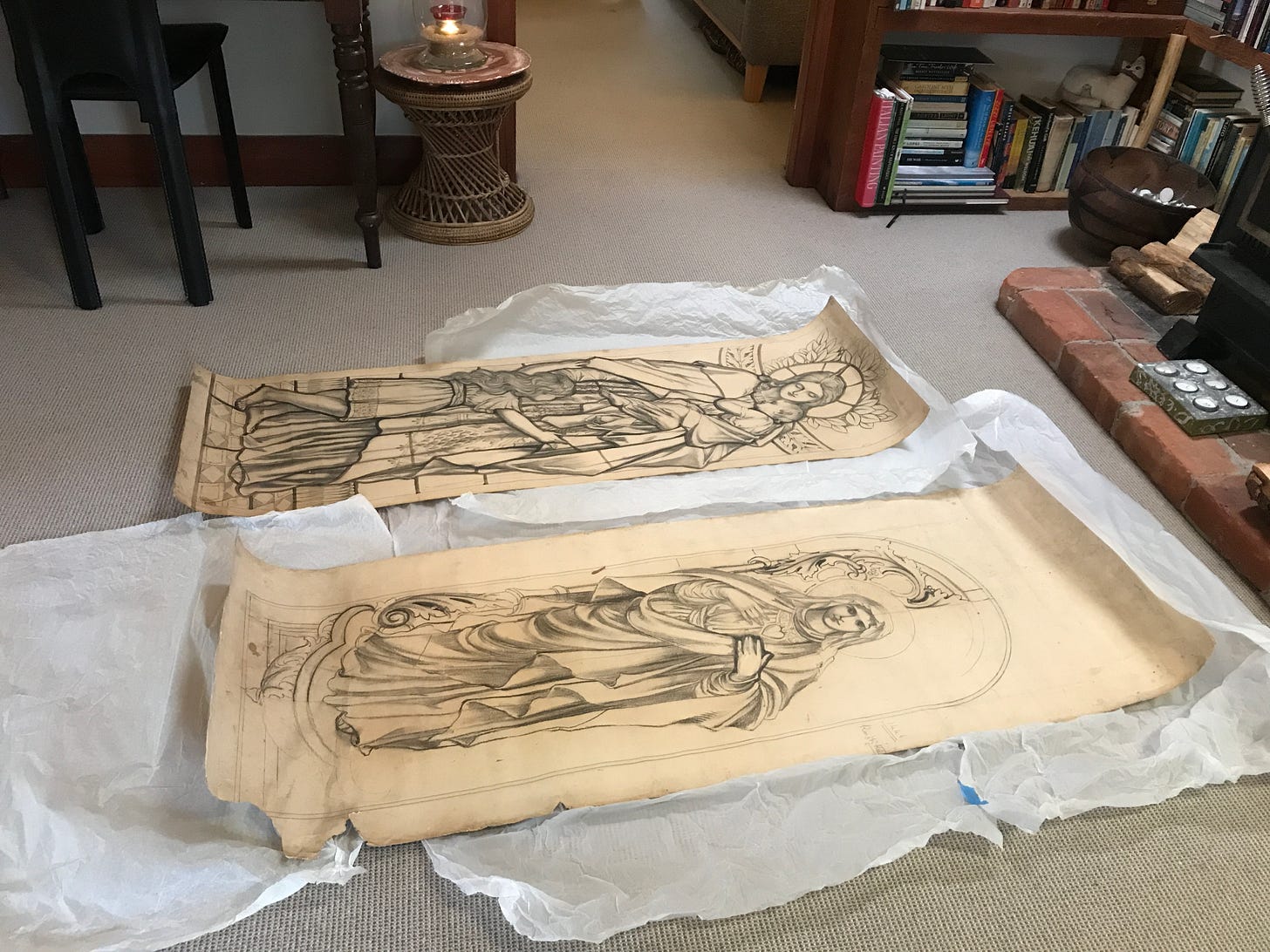

I kneel next to bone-pale tissue paper, smooth-edged, ruched; my fingers on the carpet, pressing just enough to hold myself up as Claire Beynon unrolls a person-length drawing, then another.

‘When we first moved to Dunedin, we were new immigrants setting up home from scratch and didn’t have any furniture,’ Claire says, neither of us look away from the unfurling paper as she talks, ‘So I would go to the auction, pick up things we needed. These were in a box of junk, rolled up at the back of the room. I don’t think anyone else saw them. I didn’t know what they were, but I knew I had to give them a home. They have been my companions ever since.’

Under the tissue, the heavy brown paper of Claire’s find is torn at the bottom edges. They are two working drawings, intended as guides. They’ve been held roughly, prodded, slotted away, opened and smoothed flat, tapped and marked. On the paper, in sweeping pencil strokes, faces and folds of fabric are rendered with the flat side of a pencil falling in soft lines.

I smell candle wax, coffee and the thick winter soup we will have later. I’m no-longer hungry, the forgotten coffee cools. Candlelight flickers in a glass bowl.

One drawing has a phone number and a name scrawled in the margin: Rita, and four digits, because this is the past and phone numbers were short. Rita is John Brock’s daughter. The drawings are by Dunedin stained glass artist John Brock who appears in my last two posts How art holds us (pt 1) and How art holds us (pt 2)

I picture John Brock’s hand close to the paper gently shading the underside of a baby’s foot, then one-by-one drawing the teardrop shapes on the garment the mother wears. Goosebumps ripple up my arms as I shiver. It’s almost as if he’s looking over our shoulders, as amazed as we are. Claire Beynon passes me a woollen shawl to wrap myself in.

Brian Miller, the author of Capturing Light emails Claire while we’re talking, his message chimes into our hushed conversation in real time: ‘no one kept a record of Brock’s windows, and a fire at Raffils (the glass studio where John Brock worked) burnt most of his cartoons.’

Cartoons: the name for these drawings. They are plans for stained glass that will be made. They were hardly even considered drawings, thick ink markings show where glass will be cut, where lead will bend.

These drawings are not why I’m here. I’m here to interview Claire Beynon about her recent work. She’s painting to bring a kind of peace, a heart cry to end wars, to cease fire, and I want to know about her work — this response, this holding of oneself and the world with art. And here, inexplicably, incredibly, again, is John Brock.

Steve Smart’s poem ghost print speaks into the wonder I felt as Claire unrolled John Brock’s drawings.

ghost print

The absence of hand summons a splay-finger tunnel through the suck-and-blow of ancient lifting - touch at a remove calling, recalling then’s hold to now. Gone, but stroke the rock face, handshake then and comeback, scent musks touched, grace the bride-cheek, the deer-flank, a belly-full of swung heat. Backhand ochre spattered pray calls all the choruses, retouch then and then again, all before to all since then, touch and hear and shout back grab the spread starfish, heart back and up and out from the ocean’s echoed black. Yell the latent long-dead met in stencil space met in touched shape, met in hold me, touch me, hold on, holdfast hold us all now hold here, feel here our palms’ heart beats our hands’ heat, hold now and then, and be and be.

~ by Steve Smart

I look up at the slant fall of light in one of Claire’s recent artworks. It’s huge, occupying the space of a whole wall, as wide as out-stretched arms, ‘It’s like a prayer,’ I say.

‘They are prayers,’ says Claire, ‘Attention is the deepest form of prayer. Drawing can be prayer and play. Play can lead to a moment of reverence.’

Later Claire sends me the quote from Simone Weil:

“Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love.”

~ Simone Weil

John Brock’s drawings on the floor are part of our conversation. He constructed memorial windows for dead soldiers. Another and another and another. His drawing of Mary for a Catholic Church in Oamaru captures a heart-cry like the entreaty Claire Beynon expresses in her new work.

Claire has slept outside all summer, ‘I grew up in the veld, in the dirt, loved spending nights outside with the stars. Sleeping open to the night sky has felt steadying during this time of global uncertainty and tumult. It helps me ground, listen and (re)connect.’

Tiny pin pricks of light pulse through her work, they mark spaces between every country on earth, they look like small full moons, or stars. ‘They are drawn with beeswax, chinagraph and liquin. Beeswax is a sacred material with healing and magnetic properties. Honey used to be a form of currency.’

Honey as currency. Art as healing. Constellations of connection.

‘So much can’t be put into language.’

Claire has made code languages since she was a young child writing in her diary at boarding school so prying eyes couldn’t read her thoughts, ‘They used to read our letters home. Sometimes we had to rewrite them.’ When she was allowed access to a window, she would sit for hours in the deep recess at night and watch the sky. For her recent art, Claire made a glyph language code for the ATCG of DNA, and drew the codes for every country on earth (yes, every country on earth), left to right in grid lines across a large canvas. Each country’s DNA is spaced with a luminous dot, moons, stars, ‘I set up grid lines to work in, and then as the work progresses they fall away.’ Light slants on a diagonal down through the codes, in shafts, like sunlight, breaking the distinctions between countries. North-South, East-West unified on the diagonal, ‘We are all one,’ Claire says.

‘Years ago I had recurring dreams of a woman shape-shifting into different cultural guises and skin. She straddled the earth. She was stitching the continents together with an acacia thorn. Where the edges of the different landmasses would not come together, she hefted huge boulders into the oceans, creating stepping stones or pathways that made it possible for people to cross safely. She was a surgeon, a master embroiderer.

‘I have always been interested in the heart of the mother. I saw a picture of a stork in a fire, she had her nest high on a telephone pole. Fire roared down the road towards her, and she would not leave her nest. She would not. She willed the fire to go around, and the fire obeyed and went around the nest. The mother stood her ground.’

In another work, Claire writes the words Ukraine and Russia in each others’ languages, dissolving the barriers that separate, then cuts up the letters and scatters them across the page in a grid which dissolves. Over this she paints a stork, flying towards a city, ‘She is grounded in vertical alignment, which is anchoring - the physical and the metaphysical. She is giving up a cry for peace between nations.’

Steve Smart’s poem marking time, written in response to the ancient tree drawings of Tansy Lee Moir, captures what I feel on this day with Claire Beynon and John Brock. The wonder of the student, the need to understand and then to render, or at least make the attempt.

marking time

An inward looking outward pause, charcoal blacked hands loaded ready, nine forearms forewarned still and set before a sudden dash and swerve to flush out the life, the feint and parry, the breath and rib and thrust of tree. As they prepare I remember in after-sight that dancer's practiced ease and strength, I tried to draw with a blue crayon edge to mark her movement’s moment. Proprioception requiring at least an echo, as if forming a semaphore for my witness could encode momentum, lift and pivot, inscribe the grace of drawn suspension, or craft a shorthand to re-conjure awe. Here this classes’ well armed artists form up in much better muster, feet grounded in firm chiaroscuro, gravity centered before they lunge, charcoal arcing hands knurled now knotting, swept in confident shading to reassemble ten decades' arabesque of branch and bark. A century’s growth ringed circling, marked down as gestures bound by dust.

~ by Steve Smart

As I walk days later in the dunes with my dogs, while high-grown lupins soak my trousers with beads of dew, I think about how art holds us holding each other. Claire Beynon, paints and draws towards much longed for peace; John Brock speaks into our conversation from the past; Brian Miller researches and writes the history we need; Steve Smart makes poems in response to Tansy Lee Moir’s drawings of the ancient souls of trees — all part of this this holding. And too, brave journalists like Tim Mak writing for people living now in war zones; and Hamish McKenzie and the Substack team who navigate the ethics of holding space for all of us.

Claire says, ‘I’m trying to find underlying order in the shambles, go behind the violence to see that we actually all want the same thing, which is to be loving. It’s as if I’m trying to untie knots, which is why the stitching projects are cathartic. I’m interested in the backs of the stitching. I show the backside as the front. The back is where the surprise is. A new, mysterious text reveals itself, a text that, for me, carries the potential to overcome the constraints of culture-specific language and to resonate across time and space.’

‘We are engaged with, working with, a throng of others. All of us are cataloguing each other’s working processes, dipping into the same reservoir of ideas —we each pull out a slightly different part.’

I think the back of my writing here may be: awe and the witnessing of courage in the work of these artists. The back says: Make art. Keep going. We are held.

Thank you for your attention.

Kirstie McKinnon

Links

Steve Smart’s poem marking time is from a small set called drawing breath - Steve wrote these poems when working with artist Tansy Lee Moir. There’s a wonderful audio of Steve reading these poems in his post drawing breath .

All poems used with permission.

This is a delightful interview. Steve Smart’s poetry interspersed and guiding is a lovely touch. Thank you for writing and evoking such feeling in the reader of the artists power and desire to bring love into this world.

Kirstie, thank you. Goosebumps on your arm and also on mine. John Brock again, always supportive, insistently present. "touch at a remove calling,' as Steve Smart says. And the 'heart-cry' of Claire's work. Thank you for putting this out into the world. The intricacy of the connections. Each thread in conversation with every other thread, which of course is the conversation that Claire is immersed in and offers to us for our own immersions. Words are inadequate. Except, as Steve demonstrates, as art. The oblique approach to the mystery. One of the many things that stuns me about what your piece suggests, is that this holds clues to how much we misunderstand. These connections as simply the way the fabric of the universe works. And we (or certainly, I) hardly notice. And so, dumbstruck. Awed. Heartfelt thanks to you, Claire, Steve, John Brock, and the other humans, trees and artworks that meet us here.