i.

‘Don’t try to fix it,’ my friend Miwa says, ‘This is what my teacher told me. It’s very hard not to.’

We are at my round blue and scuffed kitchen table. Miwa is teaching me the basics of how to use a calligraphy brush, she takes a sip of tea, ‘You always have the best tea,’ she says. Her eyes are warm and gentle.

It’s very hard not to want to fix a wobbly line. Mentally it feels like holding the top of a gate, resisting the urge to vault into the paddock. Sometimes I can’t resist. I wash out a trembling antennae, add more paint to a weak eye. The problem with fixing it is, it goes on and on. The antennae are now too firm and too dark, and now the eye is too splurgy.

ii.

The safety shop is light and open, knee-pads, helmets, first-aid packs. Good warm jackets, wet weather gear, torches. Pine-fresh clean floors, new rubber soles, intimations of sawdust.

I’m carrying two large stretched canvasses under my arm. I hold them as I peer at the steel capped boots, the fleece lined ones appeal to me. It’s mid-winter.

‘Want to try some on?’ The store assistant is around my age, she wears the black uniform of the store, her straight pale hair strikes a neat line down her back, her feet are clad in black safety boots.

‘Yes, thank you,’ I say, I rest the canvases against the shoe-trying-on chair.

‘Are you an artist?’

I shake my head, ‘The canvases aren’t mine, they’re for my mother who is an artist.’ I don’t tell her I feel slightly-more-important as I carry the canvases around. Maybe people will think I’m an artist whose work is dangerous, and worthy of steel capped boots.

‘I did an art class once,’ she says.

I suppress my surprise, I feel a wash of shame that it had not crossed my mind that the woman helping me might have an interest in art, this emotion is quickly followed by a dab of joy, and then a shared sense of recognition. She is no-longer: store assistant; I am no-longer: potential time-wasting customer. We become real.

‘I had an idea for three paintings,’ she says, ‘So I went to a class. The class was so much fun. I loved it. I didn’t like the three paintings I made. I put them under the bed. They’re still there I think. That was ages ago. I didn’t finish them.’

I nod. Put-it-under-the-bed. This is an impulse I can relate to. Except I feel a little sad at these canvases under the bed. Why is that? ‘The thing you make doesn’t look like the thing in your head once you’ve made it, and it hurts a little somehow,’ I say.

She nods, ‘That’s it. But. Maybe I should get them back out?’ she says.

‘Yes,’ I think this is a very good idea, though I can’t really explain why right then.

“While great art inspires us all, it also has a subtle way of diminishing us. We create an unconscious category that separates them from the rest of us. Their creativity is proof that we are not creative; their artistry is proof that we are not artistic. Yet what humanity needs most is for us to set creativity free from this singular category of the extraordinary and release it into the hands of the ordinary.”

~ Erwin Raphael McManus, The Artisan Soul: crafting your life into a work of art. HarperOne, New York, 2014.

iii.

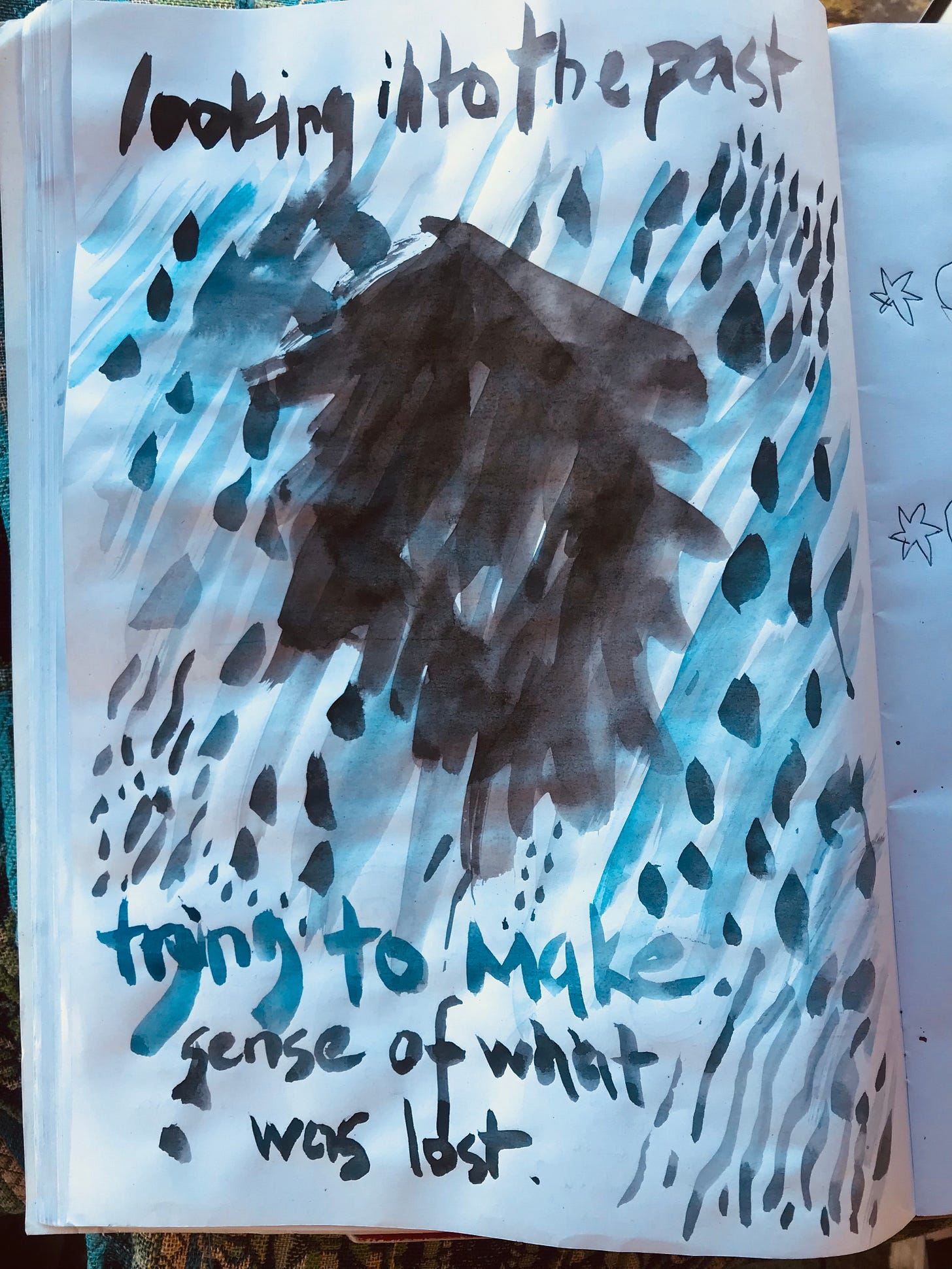

It starts with a diamond shape, black ink and the calligraphy brush. What is the past? A void, a house falling into the sky like paper ash?

There’s rain. Small swimming shapes which could be tears or fish.

“On the one hand, there are grief experiences that are concerned with loss, and they’re backward looking. We’re trying to process or figure out what we’ve lost. Then the other category of experiences is forward-looking, were we’re trying to identify how we’re going to live in the world with this loss.”

~ Michael Cholbi, New Philosopher #42, p 60.

I’m painting the first sentence of Michael Cholbi’s quote. This is draft. I don’t let myself like or not like it. I don’t think about its visual status. There’s barely any light in the room, I’m working at night, in a corner, kneeling on the floor. The page is in shadow. It doesn’t matter. I add lines of blue for rain. Little divots of black which could be tears or moments of balance.

This is unfinished work. This is draft. The not-suitable-for-watercolour paper crinkles as it dries, adding a layer of texture I don’t see until the next day. I’m exploring an idea, the outcome, the painting itself doesn’t matter. This is the mind in movement. My mind, working together with Michael Cholbi’s ideas on grief. Considering.

It’s taken me a while to get to this place of allowing. One hundred days of drawing has been a path. Miwa’s advice: ‘don’t try to fix it,’ has been a path. And somehow in allowing ordinary art to happen, a line opens across the sand.

The line opens. Ordinary art. Wonderful. And the beautiful photo conveys the wonder. It has taken work, persistence and intelligent self-observation for you to get to this point. Admirable. And what McManus says about the unconscious categories we accept is true, and baffling. Or it is to me. Because we do nothing of the sort when the endeavour is sport. A crook-kneed granny can throw a cricket ball, any kid can kick a football, and not only is no one daunted by the gold medal winners or cup holders, but the high achievers are celebrated unconditionally. Not only is a global win not felt as a negative comment on the game in the paddock, that game is seen as part of the effort. Which is exactly what it is. When half the town turns out for the round the harbour marathon, everyone is celebrated, no one shamed. The extraordinary includes the ordinary. Why the difference? Wouldn't it be great if the same applied to the arts?

Your weekly posts are a salve for my soul. 🙏🏽🩷